Digital companies are moving into the analog world to satisfy rising consumer expectations as the biggest risk they face are changes in consumer preferences.

Online marketplaces possess one of the best business models of the internet era. They produce high margins, enjoy strong pricing power and are protected from competition by network effects. Yet many of these companies are now moving into lower-margin, asset-heavy adjacent businesses like home flipping and car retailing. Why would an internet company risk its superior profitability by becoming a broker of offline transactions?

Digital companies are moving into the analog world to satisfy rising consumer expectations. The biggest risk to a dominant marketplace is not a new competitor, but changes in consumer preferences—and companies must keep up.

Today, several international online marketplace companies are moving to facilitate offline transactions. We agree with the strategy. Leading online marketplaces must change to remain relevant as consumers expect more from their shopping experiences. The future of the marketplace business model is not exclusively online nor entirely offline, but instead a hybrid of both. In the long run, digital technology in some form will touch nearly every transaction in the economy.

Online Marketplaces: Enhanced Opportunities

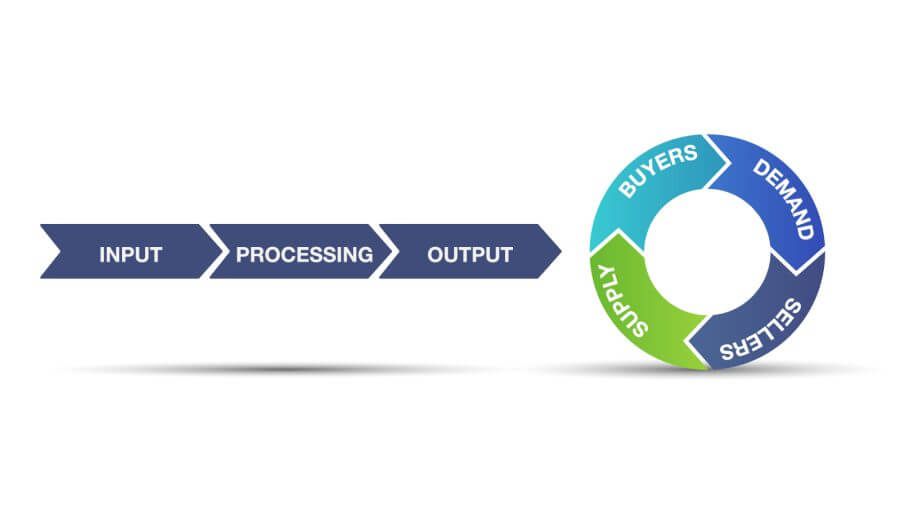

Traditional businesses operate in value chains that run in one direction: from raw materials to end consumers. In contrast, marketplaces enable transactions by others. The best visual analogy for a marketplace is not a linear supply chain, but a circular flywheel (see Figure 1). Unlike a manufacturer or a retailer, a marketplace does not buy wholesale and sell retail, it does not take inventory or balance sheet risk, it does not have significant capital needs, and it rarely touches the products or services trans- acted. Instead, a marketplace provides the venue on which transactions occur.

Figure 1 | Traditional vs. Marketplace Businesses

The internet has expanded the opportunity set for this business model. By driving marginal costs to zero, digital technology expands the convenience, efficiency, and addressable market of the marketplace model.

Consider the difference between Hyatt Hotels and Airbnb. Both are in the lodging industry, but their business models are fundamentally different.

Hyatt owns and operates hotels and charges a room rate, while Airbnb connects hosts and guests and charges a take rate. Airbnb is a global marketplace for vacation rentals—and it could never have existed before the internet.

Many online marketplaces are not entirely novel as they evolved out of newspaper classifieds. The classified section of the newspaper provided a venue for sellers of cars, houses, and general merchandise to advertise their inventory. However, classifieds’ geo- graphic reach was necessarily limited to sellers and buyers in a local area. The internet took what was a good business in the offline world and made it better: more scalable and more profitable. Categories that have proven well suited to the online marketplace model include real estate, used cars, job boards, and travel bookings (see examples in Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Prevalent Marketplaces in the Digital World

Source: Thornburg

Increasing Returns to Scale

Marketplaces defy conventional investment analysis. Economics 101 teaches the principle of diminishing marginal returns. This principle is well suited to most traditional businesses. For traditional companies, the 10,000th store, factory, or mine is not as good as its first because they have already entered the most productive markets or tapped the richest seam. Decreasing returns to scale is caused by a negative feedback effect that begins to weigh on incremental investment. After a certain point, growth becomes less efficient.

By contrast, marketplaces exhibit increasing returns to scale. Increasing returns are the result of the positive feedback effect that occurs as market- places grow, unlike the negative feedback effect that constrains traditional business growth. Marketplaces get stronger as they grow. As more buyers and sellers convene at a venue, that venue becomes significantly more valuable to all participants. This positive feedback effect (more precisely called a network effect) leads to increasing returns to scale and winner- take-all outcomes.

Marketplace Winners Take Most

Consider the example of Z.com provides much more value to both home buyers and sellers than A.com. This creates a value gap that grows at an accelerating rate as the user gap grows. This is a network effect. It not only leads to increasing returns to scale, but it also makes marketplaces very hard to dislodge.

Example | Positive Feedback Effect a Zero-Sum Dynamic in Market Share Dominance |

| Let’s illustrate how a positive feedback effect might lead to a winner-take-all outcome in practice. Suppose you want to buy a house, so you decide to browse home listings online. |

| Naturally, you gravitate toward the site with the most listings because it is most useful to you. Why waste your time on A.com, which displays just 25% of the homes available for sale in your area, when you could go to Z.com, which has 75% of available listings? Most homebuyers apply the same logic, so Z.com ends up with a disproportionate share of homebuyers. |

| On the other side of the transaction, home sellers naturally want to put their listings in front of the largest audience. As a result, all home sellers ensure their homes are displayed on Z.com, and gradually they neglect to list on A.com. |

| Compounded over time, this leads to Z.com approaching 100% market share while A.com shrinks into irrelevance. |

One cannot compete with an incumbent simply by undercutting it on price. Suppose an entrepreneur launches Y.com to disrupt Z.com. To grab market share, Y.com offers lower prices for sellers. Is this enough to convince sellers to switch their listing from Z.com? Not if there are no homebuyers on Y.com. It’s a chicken- and-egg problem. No sellers will defect unless buyers are already visiting Y.com, and buyers have no reason to visit Y.com if there is no inventory from sellers.

To get Y.com’s flywheel spinning, the entrepreneur needs to subsidize one or both sides of the network, with no assurance this heavy investment will pay off. New entrants competing against marketplace incumbents should be prepared for years of losses, particularly in low-frequency categories like real estate and autos.

The winner captures the lion’s share of customers, revenues and profits. A good example is provided by the online real estate industry in Australia, which has two publicly listed competitors: market leader REA Group Ltd, which operates realestate.com.au and challenger Domain Holdings, which operates domain.com. au. Although these two businesses compete in the same industry, the profit share is highly skewed. REA captures 71% of industry traffic, 74% of industry revenue, and 85% of industry profit (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 | Winner-Take-Most Outcome in Australian Online Real Estate

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

As discussed above, sellers naturally congregate on the marketplace with the most buyers and vice versa. In economic terms, this means that once a market- place has reached critical mass, both seller inventory and buyer traffic are nearly free. Dominant marketplaces become very profitable enterprises.

A good example of this is Autotrader (see Figure 4), the leading U.K. automotive marketplace. Over 90% of car buyer traffic on autotrader.co.uk is organic. The company spends less than 5% of revenue on advertising and marketing, a remark- ably low figure for a consumer internet company, or a consumer company of any sort. On the supply side, car dealers pay for the privilege of showing their inventory to this audience. Thus, from Auto- trader’s perspective, both consumer traffic and seller inventory are nearly free, and the main remaining costs are fixed expenses to operate the website and app. This is why a scaled, dominant market- place like Autotrader earns 70% operating margins.

Figure 4 | EBITDA Margins of Leading Marketplace Businesses in Most Recent Fiscal Year

Source: Bloomberg, Company Reports

Zillow’s iBuying Adventure and Marketplace 2.0

Despite having remarkably profitable core businesses, several leading marketplaces are taking the risk of moving into low-margin transaction businesses. We call this the Marketplace 2.0 business model. The marketplace is moving from simply being the venue where buyers and sellers meet, to actually facilitating transactions between buyer and seller, which may include taking inventory or balance sheet risk.

The starkest example of this shift from digital to analog is Zillow Group, the U.S. online real estate marketplace. Zillow’s core business is operating a website, Zillow.com, which displays virtually all residential property listings in the U.S. Zillow monetizes by connecting potential home buyers with agents using a lead-generation business model.

This is a highly profitable business. Zillow’s Internet, Media and Technology segment, which contains the core residential marketplace (as well as smaller rentals and new construction market- places), earned 38% adjusted EBITDA margins in 2020.

Yet in the last three years Zillow Group has been investing in a new venture, called Zillow Offers, which directly purchases and sells homes. This decision was criticized as an expansion into “home flipping” and Zillow’s stock collapsed by more than 50% to a low of $27 after it was announced in 2018.

The market’s skepticism was understandable. Buying and selling homes is a capital intensive and low-margin business. Zillow issued equity and raised debt to fund the expansion, diluting existing shareholders. Investors who thought they owned shared in a high-margin, as-set-light marketplace suddenly held a much riskier and more complex company. For a time, these concerns seemed well founded. Zillow’s new venture incurred heavy losses, and dragged the overall company into the red, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 | Zillow Adjusted EBITDA by Segment (USD mn)

Source: Zillow, Thornburg

But Zillow was acting on an accurate insight. Consumer preferences were changing, and if Zillow did not adapt its business model, it risked being disrupted by new startups like Opendoor, which were eager to gain share by addressing evolving consumer demands. While Opendoor had little chance of disrupting Zillow in its core business of connecting homebuyers with agents, it did (and does) have a chance in this new business of buying and selling homes directly with consumers.

We believe threats to dominant market- places come not from rivals, but from a failure to innovate at technology transitions. At these moments, consumers are up for grabs. Zillow recognized it was in such a moment and moved quickly to evolve its business model while exploiting its inherent advantage as the leading real estate 1.0 marketplace with dominant traffic scale.

“Fundamentally, we are following consumers who have been ‘uberized,’ and have grown to expect magic to happen with the simple push of a button. We’ve seen this in travel, ride-hailing, car-buying, shopping, streaming video, and more, and the time for real estate is now.” – Rich Barton, Zillow co-founder and CEO, 4Q18 earnings call, 2/19/2019.

Marketplaces 2.0: Combining online & offline channels

Zillow is not the only online marketplace moving into the analog world. Some companies were started from day one with “marketplace 2.0” business models, such as Carvana and Auto1, online used car retailers in the U.S. and Europe, respectively. These are first-party, or 1P, businesses that buy cars wholesale, hold them in inventory, and then sell them retail, earning a markup. They differ from traditional dealerships in that their only sales channel is online.

Conversely, some 1.0 marketplaces are experimenting with new transaction-based experiences, such as the Instant Offer product from the automotive marketplace Carsales in Australia, which makes consumers a binding, instant offer to trade-in their car. Instant Offer is a third-party, or 3P, business in that Carsales does not take inventory risk, but rather facilitates the trade-in from a consumer to a dealer and earns a fee. Nevertheless, Instant Offer is digitizing the trade-in transaction that until now had remained stuck in the offline world. We believe such businesses can create value, but identifying the winners, especially when the market doesn’t perceive their long-term opportunity, is crucial.

Identifying Potential Winners

Just because marketplaces have a competitive imperative to vertically integrate into the transaction does not mean this action will create value for shareholders. In our stock research, we evaluate this question on a case-by-case basis.

In general, our goal is to understand the unit economics of a business. Studying unit economics means looking at a company under the microscope: zooming in to examine the revenues, costs, and profits at the unit level, whether that is defined as an individual customer, store, or plant. This analysis helps illustrate the underlying economics of a business that may be obscured at the consolidated level or by GAAP accounting conventions.

Consider two U.S. internet companies involved in the used car market: Carvana and CarGurus. Carvana is a vertically integrated 1P online retailer. CarGurus is a 3P marketplace for used car dealers to list their vehicles for sale. As illustrated in Figure 6, CarGurus is a much better business. It is asset light and earns higher margins and attractive returns on capital.

Figure 6 | CarGurus Appears a Higher-quality Business vs. Carvana

Source: Thornburg

However, if we shift the analysis to the unit level, a different picture emerges. Let’s define the unit as a single car sold.1 On this basis, we see that Carvana is earning significantly more revenue and gross profit per unit, as shown in Figure 7. This suggests that as Carvana continues to grow, it has the potential to be far more profitable on a unit basis than CarGurus. Carvana’s vertically-integrated business model may be better able to maximize total dollar profits, which ultimately drives stock prices.

Figure 7 | Carvana’s Model Maximizes Gross Profit Per Unit

* CARG = 38m leads at assumed 4% close rate Source: Company reports, Thornburg

As marketplaces move from asset-light 3P models like CarGurus toward asset-heavy 1P models like Carvana, analyzing unit economics helps assess whether the evolution has the potential to create value for shareholders.

Digital Marketplaces have Room for Growth

As companies invest to improve the user experience and build the infrastructure to fulfill online transactions, consumers have proven willing to shift transactions online. This trend accelerated in 2020 as the pandemic forced shifts in consumer and retailer behavior. E-commerce penetration gains quickened in 2020, and we expect most of these gains to persist.

But overall digital penetration remains surprisingly low. We estimate less than 10% of transactions across the global economy are digital today. We believe in the long run almost all transactions will be digital in some form. This underlies our confidence that the digital investment thesis is in its early days.

Figure 8 | Room to Grow—Online Commerce Percent of Household Spending

Source: Euromonitor, World Bank

Just as traditional businesses have had to develop a compelling internet proposition to compete in the modern world, internet companies must go offline to provide a more seamless transaction experience. The lines between online and offline are blurring. Digitization is a continuum, not an either-or choice.

One of the more remarkable statistics reported by companies we follow was Redfin’s observation that in December 2020, 63% of homebuyers made an offer on a home they had not seen in person. This was almost double the rate from a year before, clearly indicating how the pandemic has driven dramatic change in behavior. Over half of homebuyers are using the internet as an integral tool in one of their largest financial transactions.

But this does not mean that 63% of home- buyers would be willing to close on a home without ever seeing it in person. Rather, it illustrates how online behaviors can penetrate further into a key part of the economy, without transactions moving entirely online. Consider this question: if a consumer finds a house online, makes an offer without seeing it, but then visits to tour the house and inspect it before closing—does that count as an offline or online transaction? We believe the distinction is increasingly irrelevant. Going forward, more transactions will be a hybrid.

In fact, Redfin is a great example of a hybrid digital-analog business. Redfin uses digital technologies to remove friction and improve efficiency over traditional real estate brokerages, while still employing human agents to fulfill customers’ need for expert advice.

We believe that car shopping is another large category well suited to hybrid solutions. Some consumers will always want to visit a dealership. They prefer to get advice, take a test drive and close a deal in person. On the other hand, some consumers would prefer to conduct the entire transaction from their living room. But most consumers will prefer some combination of the two. This creates opportunities not only for new digital businesses, such as Carvana, but also for traditional businesses that innovate omni-channel approaches that differentiate them from rivals unwilling to evolve.

“Divinely Discontent”—Investing ahead of Customer Expectations

Consumer expectations are not static. Preferences change and expectations rise. This is especially true in digital markets, where consumers have become accustomed to a rapid pace of improvement. The best companies not only follow rising customer expectations but invest ahead of them to widen their competitive moat.

“One thing I love about customers is that they are divinely discontent. Their expectations are never static—they go up. It’s human nature. We didn’t ascend from our hunter-gatherer days by being satisfied. People have a voracious appetite for a better way, and yesterday’s ‘wow’ quickly becomes today’s ‘ordinary’. I see that cycle of improve- ment happening at a faster rate than ever before.” – Jeff Bezos, Amazon founder and CEO, 2017 letter to shareholders

The comparison between eBay and Amazon is illustrative. On paper, eBay is a better business. This was true in 2000 and remains true in 2021. eBay earns higher margins and returns on capital, as illustrated in Figure 9. However, by failing to invest and innovate, eBay has steadily ceded e-commerce market share to rivals and confined itself to more niche and smaller-sized product categories that are less disadvantaged by its 3P model.

Figure 9 | eBay has Higher Margins, but Amazon Grows Total Profits

Source: Company reports, Thornburg

By contrast, Amazon has continuously invested in making online shopping easier, faster, and more frictionless. Through innovations like One Click checkout and Prime same-day delivery, Amazon has brought entirely new retail categories online. This investment allowed Amazon to enter much larger markets, to maximize total dollar profits, and to produce larger gains for investors.

Interdisciplinary Insights to Find Future Winners

Thirty years ago, one would have been uncomfortable buying a $1,000 item like a computer online, but now that is how most computers are sold. Ten years ago, it would have been unimaginable to buy a car sight unseen, but last year Carvana shipped nearly 250,000 cars direct to customers’ houses, making it the second-largest used car retailer in the U.S. without operating a single brick-and- mortar dealership. We are finding emerging growth companies in international markets successfully following the Carvana playbook with a several-year lag.

We observe that consumers continue to expect more from their digital experiences. They are willing to embrace online activity in more areas of their daily lives. Marketplace 1.0 companies are excellent businesses that dominate their niches, but there is no guarantee they will dominate in the future if they are unable to evolve. Companies that position for maturity too early risk being replaced by companies that are willing to go further and make life easier for consumers.

We think our global generalist model helps us recognize trends early that may elude investors focused exclusively on one region or sector. We apply our interdisciplinary insights to new markets as we conduct idea generation and fundamental stock research. While we believe digital technologies will continue to penetrate deeper into the economy for many years, we analyze companies on a bottom-up basis to identify the winners of the future.

Euromonitor International is an independent global market research company that provides strategy research services for the consumer markets. It helps businesses and academia reach their goals by offering facts and analysis on industries, countries, and consumers worldwide.

Discover more about:

More Insights

Thornburg Investment Income Builder Fund – 1st Quarter Update 2025

Taiwan Semi, Tencent, and Other “Quality” Favorites

Investor Spotlight: The Municipal Bond Tax Exemption

Thornburg’s History of Recognition

International Equity: The Power of Global Diversification